THE LAST THING HE WANTED (1996)

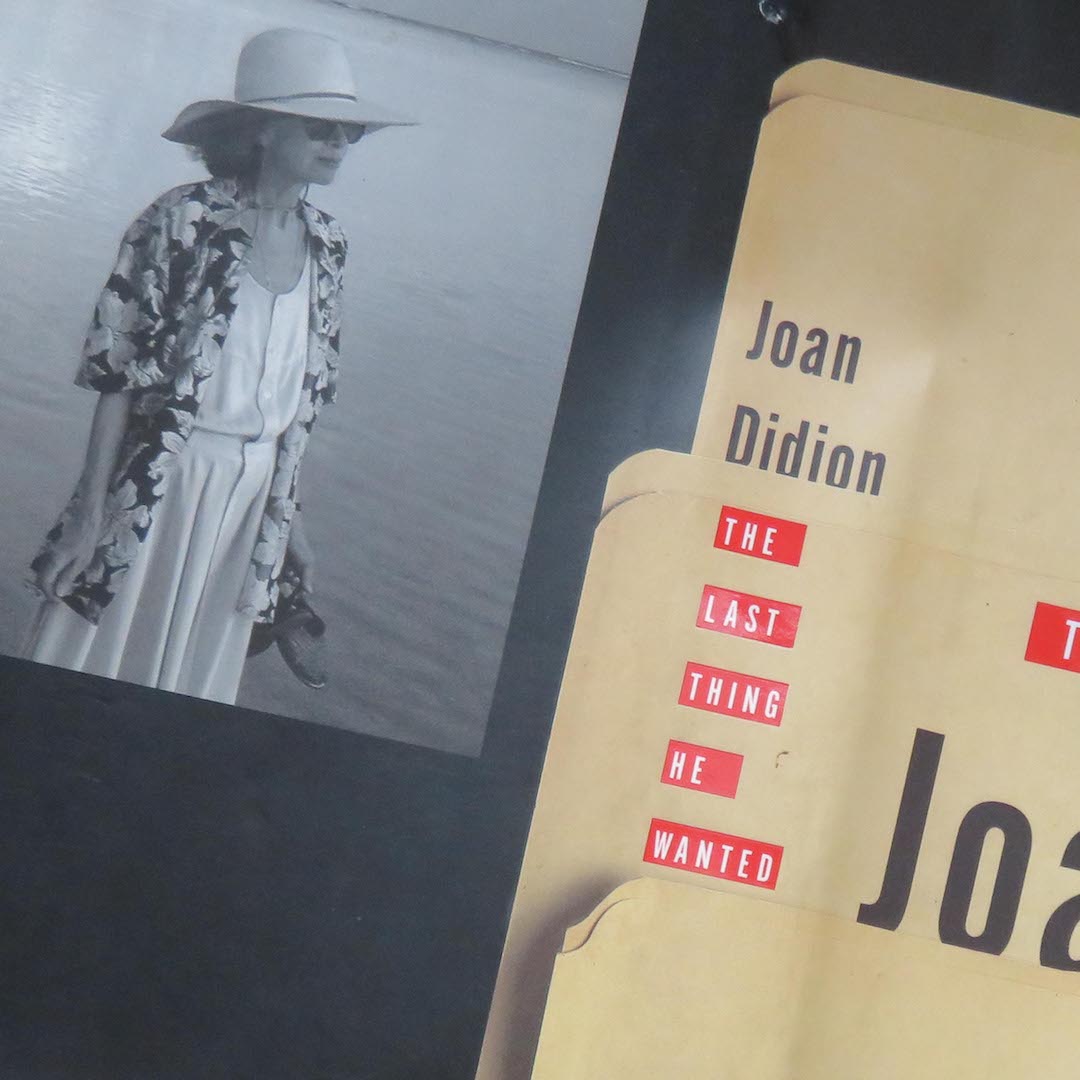

On October 7, 1996 Joan Didion was the featured author at the Unterberg Poetry Center, of the 92nd St. Y. I was on assignment (with ART BEAT) to cover the event. Excitement was palpable as she read from The Last Thing He Wanted— published by Alfred Knopf, NY a month before her appearance there. It was Didion’s first novel in over a decade. A few days later, I had the privilege of meeting her at her home (in Manhattan) for the interview. She could not have been more gracious or generous.

Interview conducted and recorded

October 11, 1996

In her own words:

Highlights excerpted from an extended interview with Joan Didon. The focus is on themes of a disaffected US Amercian culture that characterizes so much of her writing.

Dolores Brandon (DB): I very much enjoyed The Last Thing He Wanted, although I felt very very sad reading it—it’s a sobering picture of life. Let’s start our conversation with your own disclaimer: ‘this is not about Iran Contra’.

Joan Didion (JD): Well, it is about Iran Contra, that is the stuff of it, the background of it, but obviously if you set out to do a book about Iran Contra you would end up with quite a different book. I mean you put some people into Iran Contra, and then you begin to think about what would happen to those people, and that’s where it started becoming a romance as I worked on it.

DB: How are you using the term—romance?

JD: I don’t mean a happily ever after story; I mean it in the sense of an extreme tale – a story that is somehow rooted in individualism.

DB: Like a quest?

JD: Yes, a tale that doesn’t work within the society it’s in: it works outside it.

DB: The extended passage that opens the book—

“Some real things have happened lately. For awhile we felt rich and then we didn’t. For awhile we thought time was money, find the time and the money comes with it. . . . . Somewhere in the nod we were losing infrastructure . . . . There were clues all along that we should have registered, processed, sifted for their application to the general condition . . . this should have alerted us . . . but we were moving fast. We were traveling light.”

DB: . . . what was the impulse motivating that opening?

JD: That passage [describes] the impulse that started me working on [the tale]: the sense that there had been this period in American life, which was now over.

DB: A [musing] on where we’re at in our society . . .?

JD: And where we’re not! (Laughs) Yes it’s me, Joan Didio—the narrator:

For the record this is me talking.

You know me, or think you do.

The not quite omniscient author.

No longer moving fast.

No longer traveling light.

My best story was a reef dream

This is not that.

The omniscient narrator, a 19th C convention, depended on a fairly coherent society where everyone shared a lot of the same values, and would react the same way if told something. We don’t really live that way at the moment.

DB: [In your presentation at the 92Y] you said something to the effect, ‘this is a new I/eye through which people can look at the world’. A reporter, you the narrator) have as your central charager the reporter, [Elena McMahon].

JD: There’s no particular reason that Elena’s a reporter: I had to work around and justify her being a reporter in a lot of different ways. It’s a little clumsy. Logically a reporter would have more knowledge of this situation than she seems to have, But I got involved in it because when I started writing this novel, I wrote this scene in which she walks off a [presidential] campaign, and I just happened to write that because I once had a similar experience on a campaign, so I was just trying to get something on paper. Once it’s on paper, you get stuck with it, and you have this sense that this card has been dealt you that you have to play: you have to now deal with the fact that this woman’s a reporter. Otherwise if you don’t act as if everything you’ve written has some objective reality, I don’t know how you proceed at all, I mean in terms of writing fiction.

DB: The Last Thing He Wanted is your first plot driven novel.

JD: Yes, This is the first time I’ve written a novel where the plot is right up front.

DB: And, I recall you saying that you are no longer interested in the persona of the writer; that you’re interested in the technical [as in details of fact].

JD: Yes. Detail, the specific is really what [I go for]. How to lay an airstrip, for example: the Govn’t Printing Office did a series of pamphlets during the Vietnam War, called Vietnam Studies, and I got them all. There was one called BASE DEVELOPMENT published in 1968; it included a detailed map of Cameron Bay. And, had all these pros and cons of certain materials in temporary air strips; it had how to build a pontoon bridge—all this really practical stuff. I adored this book. I had two copies and still have two copies of it in case I lose one.

I wanted [the plot to have] a lot of tensile strength and not any of the conventional stuff of a novel.

DB: What is the conventional stuff of a novel that it doesn’t have?

JD: Well, it doesn’t have descriptions: it has very, very sketchy characterization.

DB: Given your career which involves you writing across genre— journalism, fiction, screenwriting—elements of each resurface here, no?

JD: It’s impossible for that not to [happen] because they’re all in my life. Actually [in this book] there is very little cross over from movies.

DB: On the other hand, I was reminded to some extent of Hollywood movies insofar you have foregrounded what is essentially a love affair— that is a daughter’s love for her father—against a thorny thicket of the political times.

JD: I think that’s true.

DB: I was struck when I heard you reading—particularly the Treat Morrison section, your cadence had a Humphrey Bogart attitude

JD: Well, that’s a section in which I’m making fun of myself as a writer, as well as the character.

DB: . . . very sardonic, very tongue in cheek, [classic old Hollywood].

JD: if you were actually to try to break this book down for a movie, you would have a very hard time.

ASIDE:The Last Thing He Wanted—made as a NETFLIX film in 2020 While the book, met critical acclaim, the movie did not; the reviews tend to bear Didion’s assessment out.

DB: So many reviewers suggest that your characters are dispirited, without spirituality : I don’t think that is true, in fact I think it’s quite the opposite.

JD: I agree:it is quite the opposite as well: I don’t think people have a very clear idea as to what faith is anymore; they mistake optimism for faith. Most of these characters of mine at least are looking for faith, are searching for faith, are in search of making that inductive leap that is involved in faith.

DB: It struck me as well, reading your earlier work— Slouching Towards Bethlehem; you describe having an attack of nausea, vertigo; you were later [talking this through with a psychologist] and concluded that feeling intense nausea was in fact quite appropriate to what you were witnessing.

JD: The summer of 1968, yes

DB: And, it seemed to me that of the two people (Treat Morrison, Elana McMahon) [in The Last Thing He Wanted, she is having quite an appropriate reaction to what is going on. She is in search of a father.

JD: That was my sense of her, yes. [Morrison] comes to [his search] a little harder because he thinks he can still effect events in the way he once could: he does not quite reach that moment of the leap into nowhere that she does.

DB: And is this why at the end, you wish they could be together?

JD: Yes.

DB: The New York Times reviewer kind of dismissed that ending; but I perfectly understood it. I mean these people are after a heart truth at this point, and perhaps together they would get there.

JD: You wish, yes. [As I was writing] the end of this book a poem kept going through my mind – a Hardy poem, The Oxen.

It begins – if someone came to me on Christmas Eve asking me to come see the oxen. And, the last line is, “I should go with him in the gloom, hoping it might be so.”

Essentially, the speaker, or the writer is saying he does not believe there was an actual manger where the oxen kneeled at the stroke of midnight, but if someone came to him in the gloom on Christmas night eve saying come see the oxen kneel, I should go with him in the gloom, hoping it might be so.”

Well, that was the exact sense I had about wishing they were together.

DB: In the Slouching Toward Bethlehem piece, you quote a line from Yeats “the center will not hold“. The center still does not seem to be holding?

JD: No it doesn’t, it did not hold, we’re kind of in free centrifugal force.(Laughter) No we’ve passed that moment when it was not holding.

DB: How might you describe your own development as a writer? What has changed, perhaps points of view you had early on, that maybe now you don’t.

JD: I used to think that the past, you know that line of Faulkner’s “the past is not dead, the past is not even past”? I used to believe that. I used to think that was true, that there were all of these levels. I used to think that the past could not in any way be escaped or erased, that it was always there with us. I stopped thinking that way. I think you can walk past the past. That’s partly what this book is about. Elena does do that.

DB: Speaking of the past takes us to history?

JD: I meant personal past, rather than history: I don’t think you can out walk history, no – although large numbers of people certainly try to.

DB: So, what’s the difference?

JD: I think what I came to see was that our personal pasts don’t have anywhere near the weight of our shared past, our historical past. I grew up during that period when everybody believed that everybody’s history was his or her own and that they made it themselves. I don’t think that way anymore. I think that to some extent our history is made for us by economic and social forces beyond our immediate control.

DB: . . . . you don’t believe in the psychological underpinnings, the ideas of say Freud. Would you say you are more of an anthropologist, and archaeologist of the human condition?

JD: I would say that the most comfortable first person I ever did was with The Book of Common Prayer—where the character (narrator) is an anthropologist, yes (laughter); she is an anthropologist who has lost faith in her own method. But she no longer believes that behavior defined or told you very much about the subject at hand. And this was a very comfortable point of view for me, it was very easy to write in that persona.

DB: But you seem to suggest we are shaped by the culture, the events of the times

JD: Not by the culture so much as by the economy; by forces beyond our immediate control. It is not actually a belief that lends itself to novels. What I mean is it doesn’t encourage, there’s nothing in that worldview that you ought to sit down and write a novel. So, it kind of creates a tension. There’s kind of a tension built in to writing a novel – for me.

DB: The US American relationship to the Caribbean? A topic you deal with so well in several of your books. You feel very strongly that the US wants to treat The Caribbean as its “lake”.

JD: The United States is not, in the conventional sense, really an imperial power in the [way] that European powers were, but there has been an area of Empire, and it was in the countries bordering on the Caribbean. And in a real way the phrase “our lake”—”mare nostrum“— [describes how we have acted as though] that was our area of influence and in many cases we thought of it as our protectorate, responsibility, and our right.

DB: TOURISM – THE RECOLONIALIZATION as the topic for a seminar [in The Last Thing He Wanted ] seemed to be a pretty apt description of the U.S. posture toward the Caribbean right now?

JD: Yeah, in some ways I think our charter now in the Caribbean is via the quote unquote drug war which has sort of enabled us to be in a lot of places where might not normally have a visible role.

DB: Is your concern for the morality of our being—in the world ?

JD: Yes. . . .the morality of lying about being there: that’s what interested me. The question of whether or not it was moral for us to be there was one question I wasn’t even ready to consider because there was this bigger question in front of it: clearly it was not a correct thing to lie about whether or not we were there. It was the lying that stopped me!

DB: To some extent Treat, as the ??? is caught up in this lie.

JD: Yes, [and he does go] to his grave as a member of a team.

DB: Do you think that that ‘s what the sad truth is?

JD: Yes, yes, I do. There aren’t too many actual casualties in Washington of this adventure.

DB: Are you ‘persona non grata’ in some political circles? I mean to what extent do you find yourself criticized, or don’t you? Do the powers that be just say well she’s a fiction writer?

JD: I am not a Washington person. I don’t think that I exist on the map so far as most policy people go.

DB: So you believe [Washington] is really that insular? That does seems to be one of the core messages in this book that in the final analysis – you/we don’t matter?

JD: That’s right. . I think it would be interesting if this country had a capital in another city, in a city other than Washington which exists entirely as a center of government: it’s a Brasilia-like situation.

If the center of government were in New York, in Los Angeles, in Chicago— almost anywhere in any one of half a dozen cities which have their own core industries, which have lives of their own apart from government, there would be more of a reality check; there would be some forced interaction between people in the government, and people outside the government. I mean it would be interesting; it would be more like Paris, maybe.

DB: In conclusion, it seems to me it’s possible to read this book on so many levels, and that there are a lot of puns and allusions to the other – 1984?

JD: No I did not intend that, no: it just happened to be the year that a lot of this stuff was happening, and it hadn’t yet broken open as it did in ’86. ’84 was the first year that I first became aware of this stuff going on, of flights, and all that stuff that we later came to know as Iran Contra.

NOTE:

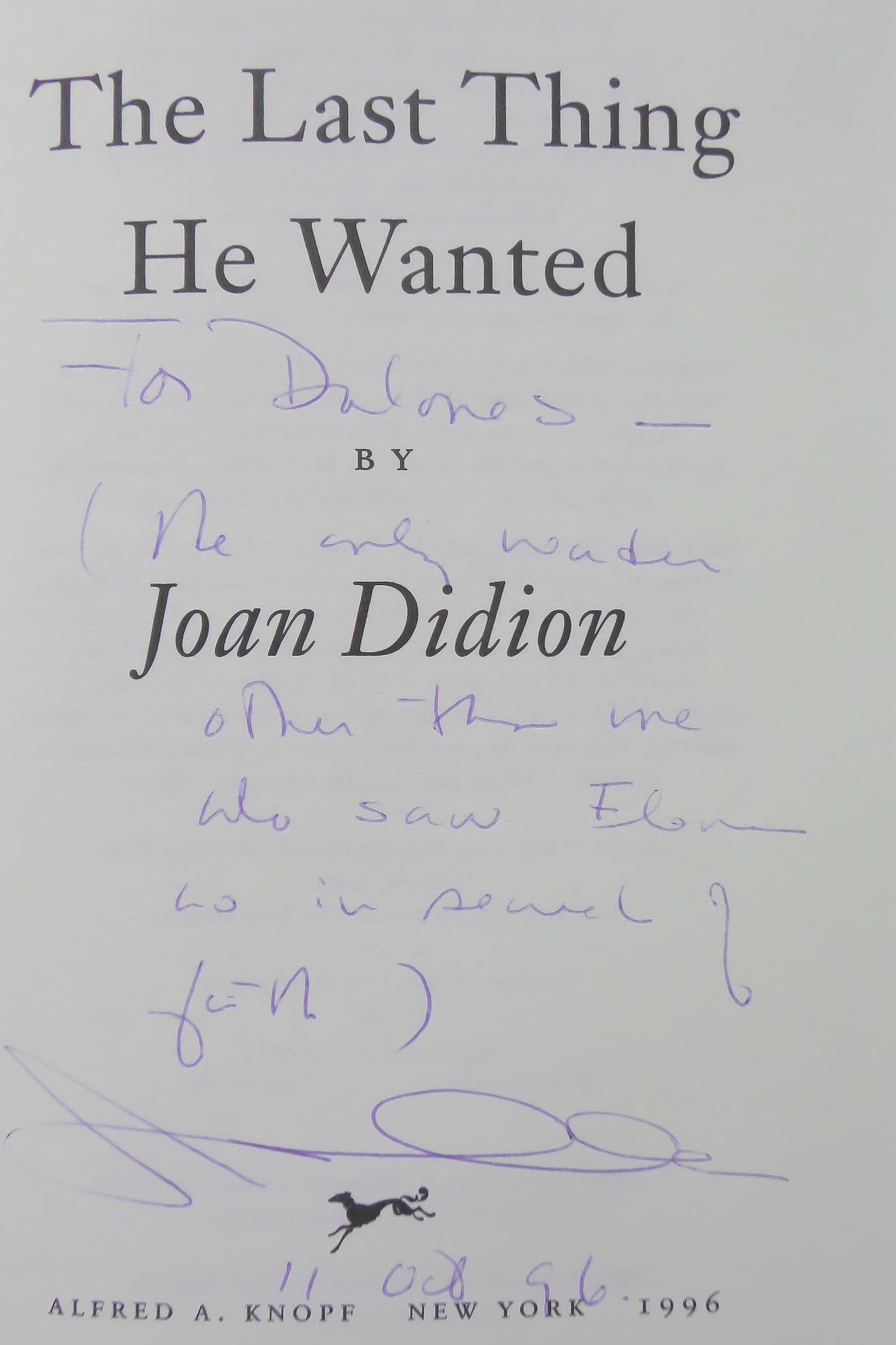

As we were winding up and I was packing up, Didion signed my copy of the book inscribed it as follows:

To Dolores, who is the only reader other than me who saw Elena as in search of faith.