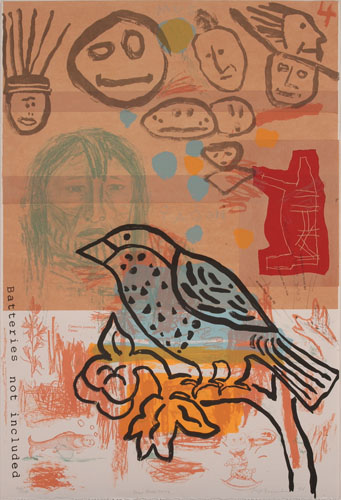

The Chief Seattle Series (1990)

With a solo exhibition of paintings at the Bernice Steinbaum Gallery(Soho, New York) in the winter of 1990 Smith expressed concern for the future of the Earth as she revisited the writings of Native American visionary, Chief Seattle.

The following radio feature (produced for CROSSROADS/NPR) profiles Smith and that exhibit.

Over the course of an extended interview Jaune QTS Smith talks candidly about the hardships of a childhood moving between foster home and reservation as her single-parent father was often away from home, traveling for his work as a horse trader.

Jaune also describes her deep passion for learning and the determined efforts she made to realize her artistic dreams.

Today Smith holds a Master’s in Fine Arts, has been awarded four honorary doctorates and is internationally renowned and collected as a Fine Artist.

In her own words:

Highlights of the Brandon/Smith interview focus on Smith’s thinking and process as an artist creating The Chief Seattle Series.

Dolores Brandon (DB): Have environmental concerns always been a central theme in your art?

Jaune Quick-toSee Smith (JQTSS): Oh, yes, it’s part of my roots; it goes way back to childhood, and listening to my father talk. I mean – I grew up in very rural places, on very rural reservations away from any urban centers so the idea of taking care of the land and nurturing it because you had to sustain yourself on the land [was ingrained]. Everything involves this sense of giving back. Everything in Indian life is about that – you have a responsibility to do this.

DB: What would you say is the motivating thread that is carried through all of the art that you’ve done?

JQTSS: I suppose abstract landscape with ideas. Groups of ideas have totally occupied me for years: ideas about the plants, animals and humans having to live together in unison. And, those explorations moved me into more political arenas like the commercial developers in New Mexico tearing up ancient Indian sites to put in housing developments – I did a series of paintings about that.

[In the Chief Seattle series] the subject matter becomes foremost. I simply took pieces from Chief Seattle’s famous environmental speech which Gladbag uses on television. It’s a very moving speech and so timely today when you think the Midwest may be a desert in 60 years because there will be no topsoil left. Chief Seattle says in his speech – they will turn this land into a desert. I mean he was a visionary so far beyond his time. When I saw Gladbag and other [vendors] using pieces from his speech, I said I have as much right or more right than they do to use this. [The difference is] I give him credit; Gladbag doesn’t which is [the way indigenous people’s history is treated]. Most of the things Indian people have contributed to society have been usurped, and someone else takes credit for it. For instance, Burbank takes credit for tomatoes – people give him credit for inventing tomatoes, which he didn’t.

DB: Is this the first time that you’ve used words in your art?

JQTSS: No, but [in the past words were] more integrated into the composition so it’s not so noticeable. This is very noticeable: I just simply directly wrote right on the canvas. Just there like a sign. Although I’m a very political person, an activist, particularly for education and the environment, I guess [I was] thinking [putting actual words on the painting] would offend the viewer, or I couldn’t get away with this or something. So, it’s sort of like coming out of hiding here to put my feelings on those panels the way I’ve done here.

In the past I’ve used pictographic forms but I discovered that people associate my Indian heritage with the pictographic forms, and then they see me in the past, and they see me as kind of a cave painter or that I’m recreating the past in some way – which is how they want to view the Indian anyway, in this nostalgic way. that’s how they view Indian people in the movies, that we were, That we don’t exist anymore, that we’re only in the past. [Even] our Indian museums encourage this kind of thing: The Natural History Museum here in New York treats as if we’re dead, they don’t talk about the living tribes or the living people.

I began feeling that I’m backed into a corner here, and I want to communicate to the viewer, and I’m not able to get past this Indian thing, so I said, ‘I’m going to have to cut back on the pictographs, I’m going to have to use something they understand.’ Well, the written word.

I began going through my books – I have quite a good collection of books I’ve picked up as I travel around the country. And, I began looking at Chief Seattle’s speeches, reading them. As I read and read and read, things began to come more into focus; I decided ‘I’ll do it the white man’s way’, I’ll write on these paintings because that’s what they understand.

I still use some of the pictographs, but now the pictographs seem to have more punch, they’re very simple and direct like street signs, and I think it communicates in a much more aggressive way.

DB: In this way you also address the refusal on the part of a segment of the art world that doesn’t want to see the work of indigenous artists as part of the modern art world.

JQTSS: {Yes] and the issue of appropriation particularly in the high art world. For instance, if say, a Joan Snider, or Stephanie Brody Liederman or Wm. Brice or whomever uses pictographic language in their work it’s not considered ancient or historical. There are a lot of artists here in New York who use signs and symbols in their work; that’s all considered very contemporary. But if we do that, or if we have blanket stripes, or stripes ‘even’ – Sean Scully uses stripes – they wouldn’t be called blanket stripes, but if an Indian person does they are called blanket stripes. There are a couple of paintings of mine that have some stripes in them, and [art commentators] refer to them as blanket stripes [as if] they’re not [an element] of modern art. It’s always interesting how [the traditional elements] get turned around.

DB: You have a Master’s in Fine Arts. How did you get such a formal study of art?

JQTSS: That took a long time. My father wasn’t educated. He was almost illiterate. And going to college just wasn’t something that our family did, nor did any other Indian family that I know of. Most of us had parents for the most part who were illiterate, or for that matter who didn’t even speak English that well. So for my generation going to college was quite a difficult task. It took me twenty-two years to get my Master’s degree. There wasn’t anyone to help me, so I would have to work jobs and go to school, and stop and work jobs, and then go to another school, and sometimes loose credits at this school, and then have to make that up in another school. It’s just that I wanted to go to school so badly. You have no idea. You have no idea what books meant to me. I think a lot, a good deal of my learning is self-taught just from books you know, that was such a luxury for me. I think that’s why I place such value on education because I know how difficult it was to get, and I know how much I wanted it, and how much I wanted to learn.

DB: Had you always enjoyed drawing?

JQTSS: From as early, as far back as I can remember. We didn’t have crayons and paper but [I was always] drawing in the dirt, and making things with rocks, and building things. I played in the woods a lot, and I was a dreamer. I think that probably has something to do with where I am today. As a dreamer, I blotted out a lot of the problems that we grew up with, and the difficulties with my father and the environment, and not having things that the white kids did, knowing that we were different. I think that my reading books at an early age carried me into other worlds, and made me want things that maybe I shouldn’t, or most other people in my position shouldn’t have wanted.

Interview date: February 1990

Copyright Dolores Brandon

Thank you for sharing Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s insight about this series and her life as an artist and activist. Your questions were superb. You also have the wonderful gift of listening. Much appreciation to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and yourself for educating public audiences about the creative process, cultural difference, and environmental and social issues at hand.

Thank you, Michelle. Jaune’s work is so beautiful, packed full of history and wisdom deserving broad circulation. It was my privilege first to interview Jaune and now to share her very generous detailed responses with those who have a sincere interest in her vision and process. Good luck with your current and future endeavors in the field of art history.