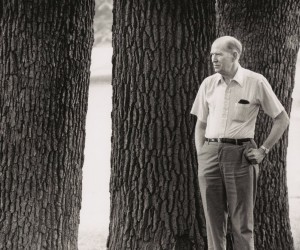

A.R. Ammons

The following interview was conducted in person with Gerald Howard 1/7/97

Gerald Howard (GH): I’m Archie Ammons editor here at Norton. I’ve been Archie’s editor since the late eighties when his former editor here, John Benedict, died. It’s a great honor and pleasure.

DB: Since I didn’t get to meet Mr. Ammons—[our interview was conducted by telephone]—I wanted you to give me a thumbnail sketch, [describe the] kind of a feeling you get in the presence of A.R. Ammons.

GH: Archie is an unusual man; he’s very laconic, not someone you know [in the way] a lot of other personalities are. He gives the impression of being greatly depressed by everything— cosmic and personal— but I doubt if he in fact is. I think he carries a lot of the country with him. You know he grew up on a farm in North Carolina. He chooses his words very carefully, and he doesn’t speak unless he has something to say; he doesn’t project his personality, he lets things come into him. So, it takes awhile to get on his wavelength. And once you do, you begin listening very hard!

DB: He doesn’t grant very many interviews and doesn’t do many readings. [With his] introduction at the 92 St Y he sort of went into a long dramatic narrative about how he had turned [the Y’s requests] down for so many years: does he not like reading publicly?

GH: I don’t think [he does], although I thought his reading that evening was exceptional: he has a kind of drop dead sense of humor and an excellent sense of timing when he wants to use it, but I don’t think he’s really comfortable being on the circuit, either being lionized or pushing himself forward. I think he really prefers that his work speak for him rather than he speaking for his work.

DB: That’s a bit of a problem [given poetry is generally not something a lot of people seek out without some public attention prompting interest]; no?

GH: I think that Archie is at a bit of a disadvantage in terms of his public profile although god knows as a poet he’s had just about every honor you could imagine, but he’s not very well known. And, I think that’s more or less his choice: there are a lot of very fine poets in this country, who both write well, and spend a lot of time going to writer’s conferences doing readings across the country, visiting professorships, all of the baggage of a modern poetic career; Archie does almost none of that. I mean occasionally, I think he was visiting professor down at Wake Forest a year or so ago, which he did because he was from North Carolina; but he’s not out there on the circuit, and he doesn’t really speak for any particular constituency; you know he doesn’t identify himself as a nature poet or a Southern poet or any other kind of poet, he is who he is: he’s not ideological; there’s a lot of ideology in American poetry. He’s rather unique, completely unique.

DB: What makes him unique?

GH: First and foremost his voice which comes out most clearly in the long poem format such as Garbage.

It’s a funny, rueful, comic, self inflating, self deflating sort of voice that he rings various changes on.

People have compared him a bit more than a little bit to Walt Whitman in this matter of voice, although Archie’s voice is nowhere near as bombastic, and hyper-lyrical as Whitman’s; I mean it’s pitched to a much different key. Another thing I think that sets Archie’s work apart from other poets is he has a strong scientific interest in the way the world works, and by the world I don’t mean government or institutions, but I mean nature. He made his living for more than a few years as an executive for a scientific glassware manufacturer, and if you look at a number of his poems they exhibit very intimate knowledge of biological, geological and meteorological processes; you could learn a lot from Archie Ammons’s poems about the mechanisms of nature.

And I think he sees things in an impersonal way; he looks at things in a rather cosmic perspective; but then all of a sudden he’ll shift that perspective, and you’re back on the planet earth again with a rude or funny observation.

DB: He is very funny; his poetry is intensely personal, the anger, the humor. You could really know everything you would want to know about him from his poems.

GH: Except who he really is. Although you learn a lot about A.R. Ammons, this is not confessional poetry in any shape or form; and I don’t want to put Archie or his work on the couch, but I think a lot of the humor is used as a way of deflecting attention to himself, and he’ll tell you something about himself but he won’t tell you everything: I don’t think he feels comfortable that way. He’s an older style American— formal, a Southerner; southerners have an inherited formality in their ways of dealing with the world that a lot of other Americans don’t. They’re raised upright.

DB: What might you say are his primary themes?

GH: If anybody bothers to pigeonhole, him it’s as a nature poet, but his take on nature is one of process, rather than celebration. I mean he doesn’t write odes to flowers and trees; he looks at nature from a distance and with a scientist’s scrutiny. I think he’s immensely curious about the mechanisms of the universe large and small. I think Archie thinks a lot about God’s intentions, and as manifest in the universe. I think he would fiercely resist the tag of religious poet, but I do think there’s a more than a tinge of the Transcendental in him, uppercase T as in Emerson.

DB: Yes, there is a deeply spiritual aspect . . .

GH: Which comes out of his curiosity, and occasionally sense of wonder, but he keeps it under control.

DB: He is attracting a fair amount of attention now, is he not?

GH: Yes, but he hasn’t lacked for that for the last couple of decades: if you look at any anthology of post-war American poetry that makes even a pretense of being comprehensive, there will be 3-4 poems by A.R. Ammons in there. So, in that limited sense, Archie’s already part of the canon. But again, not being particularly confessional, not being ideological, not belonging to any particular political or aesthetic party, and also not being one to draw attention to himself, he can kind of fade into the woodwork at times, but I think he’s partially because he won the National Book Award for Garbage, and partially because he’s made himself a little more available than previously for readings, and for interviews, I think his profile his higher now than it has been for quite a while.

DB: If you were doing a profile on him, what would you think would simply have to be said about him?

GH: That Archie Ammons is a great American poet who doesn’t carry himself that way: that he’s an exceedingly dedicated artist who works at his craft because he has to, not as a means to get attention; for Archie the writing is a reward. The other thing I would say is he’s a marvelous teacher, and generations of writing students have come through Archie’s classes at Cornell and have come out of it touched in important ways)

DB: The long poem, there aren’t many people who write in this style to the extent that he does . .

GH: No. There really aren’t, let alone on adding machine tape. I think the fact that he composes his poem on rolls of adding machine tape and that the width of the adding machine tape dictates the width of the line is a kind of artificial constraint that Archie selects that allows him to go ahead and write: it gives him boundaries within which he can play: there’s Robt. Frost remark about playing tennis without a net, if you don’t have any rules, you can be paralyzed by all that freedom. Whereas,if you give yourself some artificial constraints, well you can accomplish from within those constraints. But it’s anything but a Beatnik exercise: I mean there’s enormous discipline within the way Archie goes about composing these poems, but there’s also a spontaneity to it.

DB: Enormous spontaneity. I notice, too the punctuation. He doesn’t use periods, except at the end [of a poem]. [Instead, hee employs the] colon, semi-colon, comma. I guess that’s a sense of the ongoiness?

GH: Yes. I think he sees life as an open-ended process, and I think the long poems express that sense

DB: His method seems to be very free associational, as well as meditative in the sense that he is centered in some spot.

GH: But it bears mentioning that he doesn’t just write long poems because he can’t quite discipline himself within shorter poems: he’s a wonderful poet in a compressed space. The first book that I published here is “The Really Short Poems of A. R. Ammons, and within a very brief compass he can do something almost oriental in its precision and beauty: and when the antic spirit is on him he can write very funny brief poem: the one that I like—it’s a two liner— it’s called Their Sex Life; one joke on top of another. That’s Archie Ammons: no one else would write that poem.

DB: He does have a very playful side; it’s very engaging and endearing, I think, both personally, and [when] reading him. I also thought of haiku: nature, the cosmic, that sort of quick turn. He says: I don’t revise, that’s the kind of type I am.

GH: He does revise somewhat, word changes. If he has a bad day at the typewriter, I suspect he may just take what comes out an put it in the circular file. But I see the poems as they are Xeroxed on adding machine tape, I mean the manuscript I get is the Xeroxed adding machine tape text, so he’s playing it pretty honest.

DB: Well, he’s very modern in that regard, I think of John Cage.

GH: That’s an interesting comparison, John Cage: the kind of ability to accept accident and contingency again a perfectly American point of view, a kind of practical and cosmic at the same time.

DB: You know who else I thought of when I was reading him – e. e. Cummings?

GH: Yes, yes, exactly although Archie doesn’t push his experiments as in extreme a direction and I think he would probably deny it like crazy. You know you should really talk to Harold Bloom if you can about Archie, it would be difficult, but Bloom is Archie’s great champion and Bloom really believes that Ammons is to contemporary American poetry as Emerson was to 19th C American poetry and thought.

Copyright: Dolores Brandon All Rights Reserved:

Permission to reproduce requested: contact brandon.dolores@gmail.com